Take me with you

On Zakwato & Loglêdou's Peril, "loss," and how failure sustains

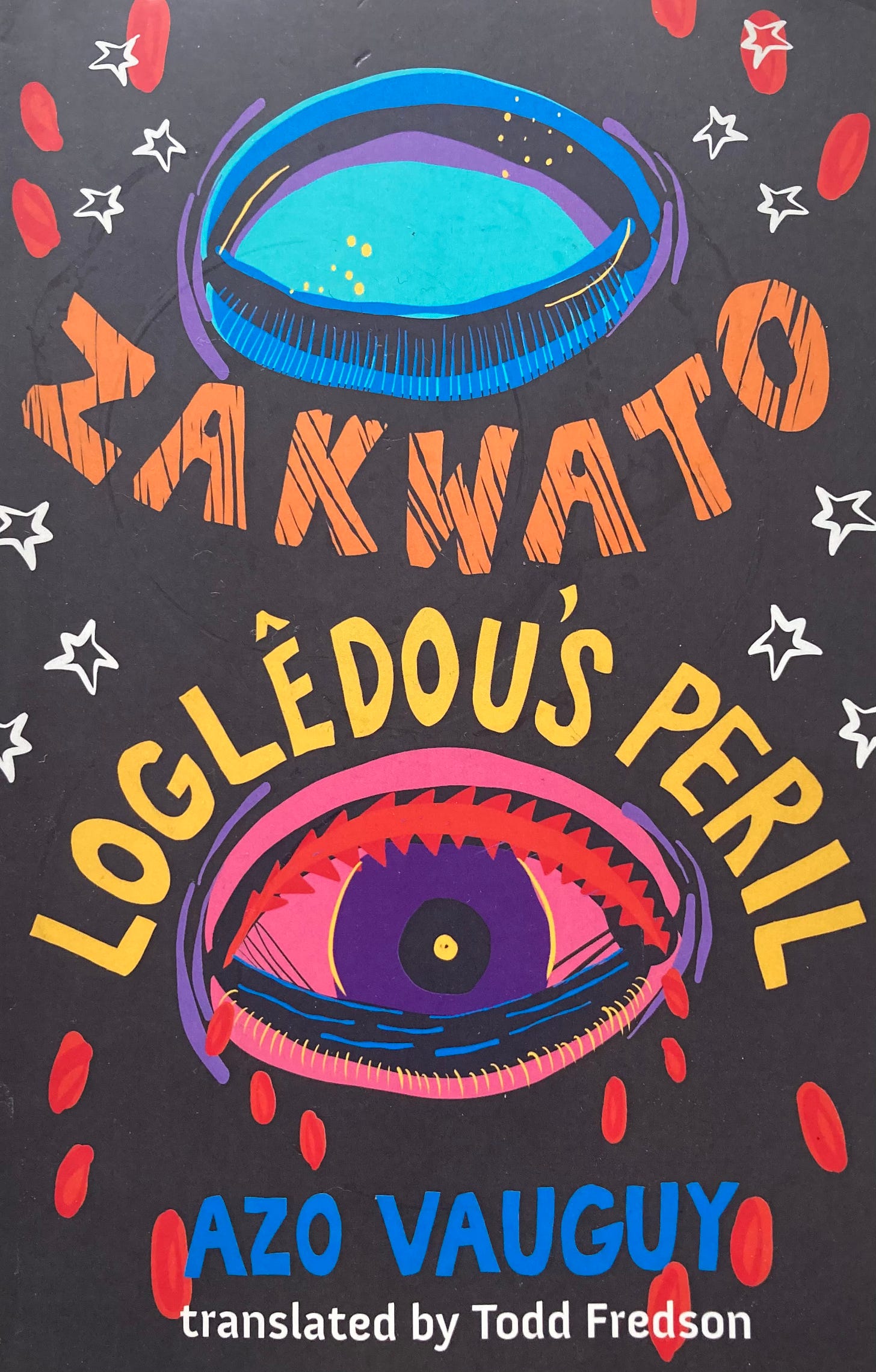

Zakwato & Loglêdou’s Peril by Ivorian poet Azo Vauguy, translated from French by Todd Fredson.

I don’t like to mourn what’s “lost in translation.” To me, that terminology boringly misses the point—at best. But there’s a line in Todd Fredson’s introduction to his amazing translation of Zakwato and Loglédou’s Peril that considers this loss in a way I find astounding.

“What wildness could exist were everything able to be made to operate on our terms—were everything made comprehensible.”

This comes after Fredson describes years of conversations with the poet Azo Vauguy in Abidjan discussing the Bété cultural context the book is grounded in. After Vauguy’s death, Fredson turned to the Ivorian literary and academic community to keep learning. He spent fifteen years working on this translation.

There was no giving in to the “loss” of translation for Fredson, but more, an acceptance that not everything in the world can be fully consumed by everyone else. This honors the complexity and rootedness and the specificity and how we hold our own cultures inside us and inside our language.

In the time we’re in now, I find this failure sustaining. It’s not losing. It’s process. When it can seem possible to know everything, translation reminds us that we can’t. And in that limit, we encounter wild complexity, even if we can’t fully touch it.

Zakwato is one of my favorite books of translation that I’ve read in the past few years, maybe because of the depth of the work put into the translation and the giving in to never going deep enough. The book is different from anything I’ve read before. It feels alive in English, bubbling, twisted, surprising, and I can sense the edges of what isn’t mine to fully know.

Plus: I’m a sucker for epics in translation. My Brilliant Friend, Beauty Is a Wound, Zakwato: take me with you even though I don’t know exactly where I am. I trust you, translator, to let me get lost enough.

–Jennifer